When AI outshines doctors

AI might be becoming better than doctors at diagnostic reasoning. What now?

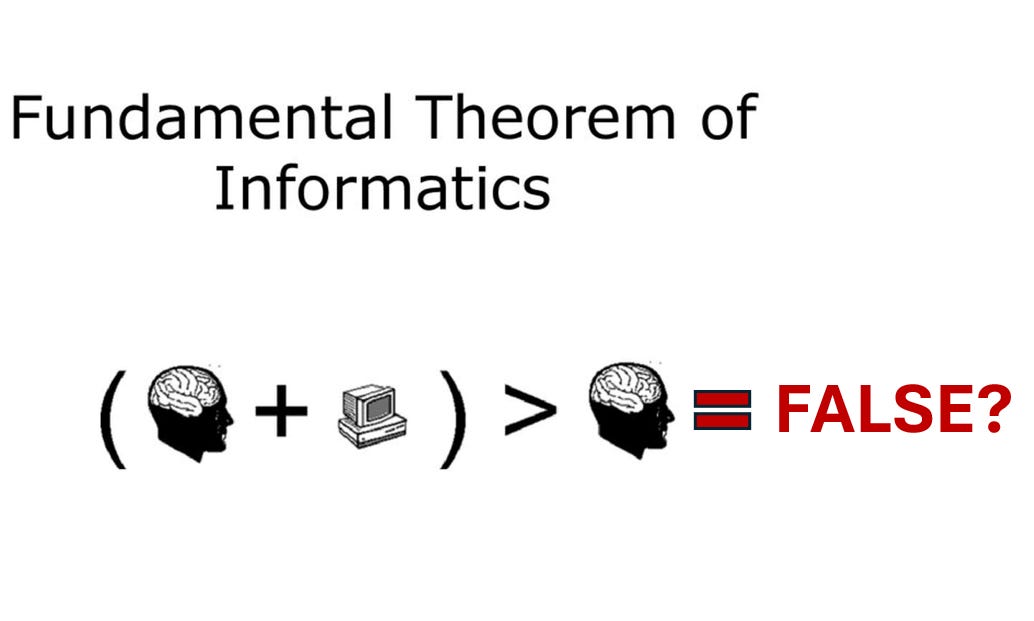

In 2009, Charles Friedman proposed a “Fundamental Theorem of Informatics” that stated “A person working in partnership with an information resource is ‘better’ than that same person unassisted.” This was the underlying principle for the value of informatics in medicine: clinicians armed with the right data driven tools will always be better at taking of patients than those without.

What if this is no longer true with AI?

A recently published paper from colleagues at Stanford reports a single blinded randomized controlled trial assessing whether access to a large language model (LLM) chatbot improved physicians' diagnostic reasoning. 50 physicians were randomized to an LLM-assisted group (the physician had access to a LLM chatbot such as ChatGPT in addition to conventional reference tools) or a control group (no LLM but access to conventional reference tools) and asked to assess written clinical vignettes and generate lists of diagnoses that were then later scored by a group of expert physicians.

There was no significant difference in overall diagnostic performance scores between the physician + LLM group (76%) and control group (74%). However, the LLM alone (without any physician input) was by far the most accurate of the three groups with a median score of 92%.

The results were surprising to many in the field as it seemed to challenge the prevailing assumption that human + AI is better than human or AI alone. In fact, physicians interacting with the AI seemed to have had a negative effect on the AI’s ability to make accurate diagnoses!

What then, differentiates physicians from AI, and how do we teach it?

As an internal medicine physician, I have always taken great pride in our specialty's diagnostic reasoning skills. It is important to recognize that we cannot draw definitive conclusions from a single study. Further, generating a differential diagnosis from a pre-written clinical vignette is also an artificial and narrow task that does not fully capture the complexities and nuances of real-world diagnostic reasoning, which requires skill in collecting and synthesizing relevant information from disparate sources over time.

However, I believe it is time to acknowledge that superior diagnostic reasoning is no longer what differentiates our value in the era of AI. If the scaling laws for neural networks continue to hold true, it is highly probable that in the near future, AI will consistently outperform physicians.

I would also argue that superiority in this narrow cognitive task should not be the defining characteristic of a physician’s value.

A physician’s job is to improve the health of our patients by preventing, treating, and managing disease. While accurately identifying the correct diagnosis is undoubtedly a crucial step in this process, it is just one of many essential components.

What truly sets the best physicians apart from others is their capacity to deliver comprehensive, patient-centered care that goes beyond mere diagnosis. They cultivate trusting relationships with their patients, deeply understand individual circumstances, beliefs, and preferences, and guide their patients through complex medical decisions with empathy and compassion. They tailor their medical knowledge and expertise to the unique needs of each patient, ensuring that the diagnostic and treatment strategies are not only technically correct but also aligned with the patients’ values and goals and successfully executed within a complex healthcare system.

While some may label these qualities as the "art" of medicine, I believe this term undermines the fact that these qualities can be systematically identified, nurtured, and taught as core competencies in medical education.

As we train the next generation of physicians, we need to intentionally think about how to cultivate and prioritize these essential human skills alongside traditional medical knowledge. This means redesigning medical education to place greater emphasis on effective communication, empathy, shared decision-making, and managing complex systems. We must provide aspiring physicians with the tools and guidance to navigate complex patient interactions, build trusting relationships, and deliver personalized care that respects each patient's unique needs and values.

Nowadays, when I attend on the medical wards working with trainees, I start the week by telling them that it is not important for them to memorize any data or medical guidelines; they are encouraged to use the computer to look up any information they need, including medical references or even a LLM chatbot, when they discuss patients on rounds. Instead, I emphasize that the primary focus is for them to leverage these tools to confidently make an assessment, reach a decision that the patient is also comfortable with, and successfully carry out the care plan as a team. The ultimate goal is not simply getting the right diagnosis, but providing the best possible treatment to improve the patient’s health.

We need a new paradigm for building “human + AI” teams

Giving doctors access to an LLM chatbot is a start, but does not constitute a true human-AI team. Designing such teams and its enabling technologies is a wide open space for exploration. In a previous Byte to Bedside post, I discussed the concept of “cognitive integration" between AI and physicians, where the AI's capabilities are seamlessly integrated with the physician's skills, creating a complementary partnership that enhances the strengths of both.

As AI becomes more consistently proficient at diagnosis and reasoning tasks, we must consider how these capabilities can be leveraged to enable new healthcare delivery models that can provide high-quality, accessible care to a larger population at a reduced cost. For example, imagine a primary care practice where each physician is supported by a team of AI agents that can triage patient concerns, provide personalized health education, monitor chronic conditions, and even suggest evidence-based treatment plans. This AI-augmented approach could allow a single physician to effectively manage a much larger patient panel while maintaining high-quality, individualized care. Patients would benefit from improved access, reduced waiting times, and proactive, data-driven health management, all at a lower cost compared to how care is delivered today.

These new AI-enabled care models will bring drastically different unit economics and scalability. It is time to move past the current model that relies on a physician personally seeing every patient to render a diagnosis and treatment plan - an approach that is not meaningfully different from 100 years ago.

The fundamental theorem of informatics still holds true, but needs an update

Humans + computers > humans or computers alone, sometimes.

We need to better understand the following: 1) what the "human + AI" team looks like, and 2) what are the specific tasks for which this collaboration outperforms humans or AIs alone.

For the task of diagnostic reasoning from text vignettes where the human + AI team is just giving physicians access to a LLM chatbot, AI may be giving physicians a run for our money. But for the task of taking care of patients, I am betting on the human + AI team. The work now is to figure out how to be build the team.

References

Goh E, Gallo R, Hom J, et al. Large Language Model Influence on Diagnostic Reasoning: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(10):e2440969. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.40969

I have no doubt AI tech will far exceed our abilities in the “cognitive” domains of medicine in the relatively near future. Even those skills we now think of as uniquely “human” such as building trust and demonstrating empathy will soon be eclipsed by AI. Sure, there will be some that never “trust” AI as they would a human, much like there are some that still don’t “trust” airplanes. For most, the value proposition will be too great to ignore. 24-7 access everywhere to inexpensive cutting edge medical expertise delivered in a manner optimized uniquely to the patient and their communication preferences.

It’s interesting that you didn’t mention physical examination as one of the uniquely “human” physician abilities. I think the human touch might be one of the more difficult things to replicate, although certainly not impossible. Robotics have already made their mark in many surgical fields, but these are still largely surgeon assisted. AI is already excelling at reading imaging studies. So far I haven’t met an AI or robot that can perform a Phalen’s test for carpal tunnel syndrome, but seems like something Elon’s Optimus could easily learn.